What is Chikungunya Virus and How Does it Spread?

Chikungunya (chik-en-gun-ye) is one of the lesser known viruses transmitted to humans by mosquitoes, but it is gaining notoriety in the Western Hemisphere since its introduction to the Americas in 2013 on several Caribbean islands. Certain parts of Africa, Southeast Asia, and India report the largest number of cases each year. Areas with known transmission should consider extra preventative measures for newborns, older adults (65+), and people with medical conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease. Chikungunya disease can result in painful and disabling symptoms, but it is rare to see complications resulting in death. If a person has been infected, their body will likely build a tolerance for protection against future infections.

Signs and Symptoms of Chikungunya Virus

Common Symptoms

- Chikungunya symptoms typically begin with a fever three to seven days after exposure.

- Following the fever, individuals experience significant joint pain or stiffness, usually lasting for weeks or months.

- Other symptoms can include muscle pain, headache, rash, or joint swelling.

Treatment of Chikungunya Virus

- Currently, no specific medications exist to treat chikungunya virus infection or disease.

- Treatment for symptoms includes rest and the use of acetaminophen to relieve fever and pain.

- Patients should also be advised to drink plenty of fluids if diagnosed.

- If anyone has recently traveled to a known endemic area and is displaying any symptoms of chikungunya infection, they should consult their physician immediately.

Chikungunya Misdiagnosed as Dengue

Chikungunya infection has symptoms similar to dengue infection and can be misdiagnosed in areas where dengue is common. Both infections can result in fever, headache, and muscle aches. Lingering joint pain, with some adults experiencing months of arthritis, is the main difference for individuals with a chikungunya infection.

Chikungunya and the United States

Beginning in 2014, the United States began reporting travel-associated chikungunya cases among returning travelers from areas in South America and the Caribbean. Soon after, locally acquired cases (when mosquitoes in the U.S. transmit the virus to people) were identified in Florida, Texas, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. By 2015, chikungunya became a nationally notifiable condition in the U.S., and health officials tracked both travel-associated and locally acquired infections through ArboNET, the national arboviral surveillance system managed by the CDC.

After several hundred imported cases and sporadic local transmission in 2014 and 2015, no locally acquired chikungunya cases have been reported in U.S. states or territories since 2019. However, travel-associated cases continue to occur among U.S. residents returning from regions where chikungunya virus circulates, including a higher-than-expected number of travelers returning from India in 2024. 199 travel acquired cases were reported in 2024. Because mosquitoes can become infected by feeding on infected humans and then spread the virus to others, there remains a risk of new local outbreaks if infected travelers return to areas of the country where Aedes mosquitoes are present.

Unlike many other mosquito-borne viruses in the United States—which often have an animal reservoir—chikungunya virus relies primarily on humans for transmission. Mosquitoes become infected when they feed on a person with the virus and subsequently spread chikungunya by feeding on other people. Regions of the U.S. with climates favorable to Aedes mosquitoes remain at the greatest risk for local transmission events, underscoring the need for continued monitoring, mosquito control, and personal protection efforts.

A Global View of Chikungunya

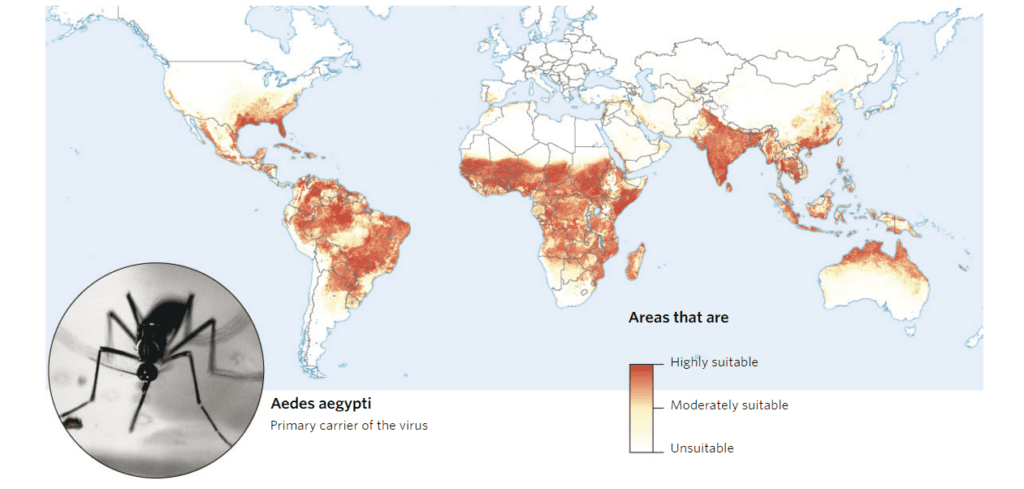

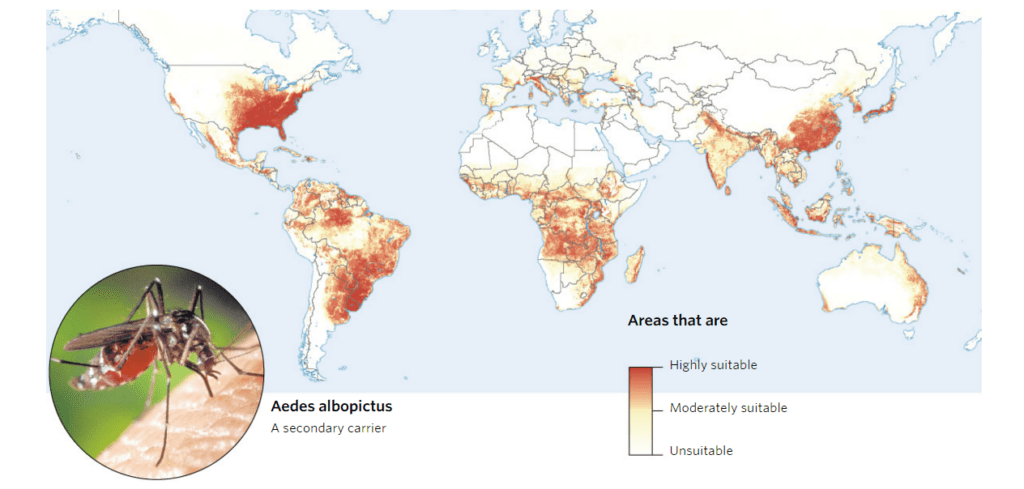

Chikungunya is most often transmitted by Aedes aegyptiand Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. These species are also responsible for the transmission of dengue virus, yellow fever virus, and more recently Zika virus. The below maps highlight parts of the world that provide a suitable environment for each species.

Know Your Aedes Mosquitoes

Aedes aegypti, the yellow fever mosquito, is characterized by a silvery-white “lyre-shaped” pattern of scales on its thorax. It is a peridomestic species found not far from human dwellings. They are primarily early morning or late afternoon feeders, but females can also take a bloodmeal at night under artificial illumination. Typically, Ae. aegypti fly only a few hundred yards from their breeding sites.

Aedes albopictus, the Asian tiger mosquito, is a black mosquito with distinctive silvery-white scales and a white “racing stripe” on its thorax. First reported in the U.S. in 1983, this species has become one of the most challenging mosquitoes to control and, unlike most mosquitoes, actively bites during full sunlight. Beyond being a daytime biting nuisance, the Asian tiger mosquito is also capable of transmitting several diseases, including

West Nile virus,Zika, dengue, and several forms of encephalitis as well as Chikungunya. The presence of this invasive species has become a major public health concern in many locations across the country.

Both species utilize containers to breed, and educating the public on how to eliminate their backyard larval habitats

is one key to keeping these invaders under control. Larvae can be found in a variety of artificial containers, including buckets, tires, cans, and flower pots. Homeowners should also inspect rain gutters for clogs, gardening equipment, and backyard children’s toys.

Controlling Aedes aegypti/albopictus and Chikungunya

An Integrated Mosquito Management (IMM) program is essential to helping prevent mosquito bites and transmission of serious vector diseases in the United States. As part of an effective IMM program, VDCI recommends a 4-pronged approach to target all phases of the mosquito’s life cycle.

1: Public Education

Community understanding of how to properly eliminate mosquito breeding habitat and take personal protective measures is critical. Furthermore, distribution of educational pieces is important for treating symptoms and aids public health officials in identifying chikungunya problem areas.

2: Surveillance

In order to understand the risk and address the threat appropriately, it is critical to determine the mosquito distribution, density, and species composition throughout the target area. Surveillance will also provide direct evidence of an increased transmission risk of chikungunya.

3: Larval Mosquito Control

When mosquito larvae are detected in an area, trained and experienced ground crews reduce breeding habitat when possible, then preferentially apply Bacillus thuringiensis var israelensis (Bti) to remaining areas of standing water, stagnant pools, and water-holding containers. Aerial and ground application of larvicide via ULV equipment can provide control in hard to reach container habitats.

4: Adult Mosquito Control

VDCI recommends the deployment of two-person teams to conduct targeted ULV applications combined with residual “barrier” applications via backpack applicators to mosquito harborage areas near homes and other structures. In addition, when the disease risk warrants it, truck and aerial ULV applications should be utilized to reduce the adult mosquito population. When combined with our larvicide efforts, these methods have proven highly effective at significantly reducing local populations of the target mosquitoes.