Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

What is Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and How Does it Spread?

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is a vector-borne disease that is transmitted through an infected tick carrying the bacterium Rickettsia rickettsii. The infection is usually the result of a tick bite; however, infection may also occur when an individual’s skin is exposed to an infected tick’s blood or feces. Exposure could occur during tick removal from a human or pet. The disease was first described in the Rocky Mountain region of the United States in the late 1800s. It is most common in the south Atlantic and south central regions of the U.S. however cases are reported from Canada, Central and South America, as well as almost all 50 states. April through early September, when ticks are most active, is when more individuals become infected, with medical professionals seeing the greatest number of RMSF cases in June and July.

| Symptoms of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever |

- RMSF symptoms often develop within the first few days of a tick bite; however, some individuals may not experience symptoms for up to two weeks.

- Traditionally RMSF symptoms include fever (103° – 105°F), chills, headache, abdominal pain, loss of appetite, vomiting, and muscle pain.

- The distinctive RMSF rash may develop several days after the onset of a fever, with some patients (approximately 10%) never developing a rash. The rash typically begins as little, non-itchy, pink to red spots or blotches that start on the wrists and ankles. As the rash spreads, it can continue to the palms of the hands and soles of the feet as well as move up the arms and legs and towards the core of the body.

- When treated early with antibiotics, most cases see a full recovery.

- Doxycycline is the most commonly prescribed antibiotic for individuals of all ages.

Early Detection of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever is Key

![]() If not diagnosed and treated within the first few days after the symptoms begin, RMSF can become a severe and sometimes fatal illness. Health care providers are urged to move forward with antibiotics when RMSF symptoms are present, and/or a significant suspicion of an RMSF infection exists. The delay of antibiotics, while waiting on a lab report or an initial test providing a negative presence of Rickettsia rickettsii, could result in a severe case that may lead to greater health concerns with the heart, lungs, or brain. If a petechial rash surfaces, where spots appear red to purple, this is a sign that the disease is progressing to severe. Properly educating the public on the tick vector species and taking preventive measures should be a goal in communities where RMSF cases have been reported.

If not diagnosed and treated within the first few days after the symptoms begin, RMSF can become a severe and sometimes fatal illness. Health care providers are urged to move forward with antibiotics when RMSF symptoms are present, and/or a significant suspicion of an RMSF infection exists. The delay of antibiotics, while waiting on a lab report or an initial test providing a negative presence of Rickettsia rickettsii, could result in a severe case that may lead to greater health concerns with the heart, lungs, or brain. If a petechial rash surfaces, where spots appear red to purple, this is a sign that the disease is progressing to severe. Properly educating the public on the tick vector species and taking preventive measures should be a goal in communities where RMSF cases have been reported.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and the United States

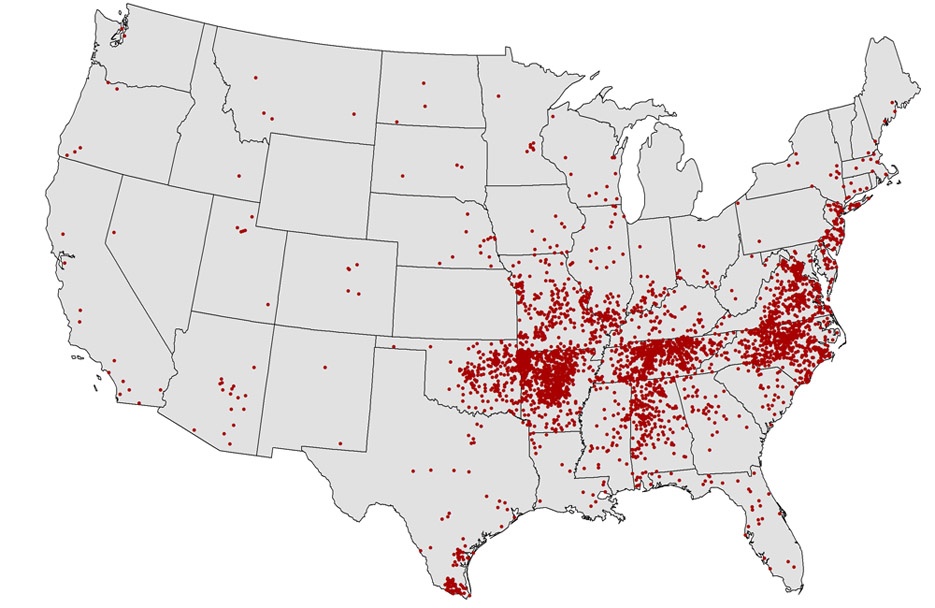

There are approximately 2,000 cases of RMSF reported each year in the United States. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports over 60% of RMSF cases within the U.S. are from North Carolina, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Missouri. Currently, the American dog tick is the main vector to transmit Rickettsia rickettsii in the U.S. With the ability for the infection to turn severe or deadly without proper diagnosis and treatment, personal preventative measures and integrated tick management (ITM) programs should be executed in endemic areas to help reduce this significant public health concern.

Source: CDC – Cases Reported to CDC of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (U.S. in 2014)

Tick Talk on the Dermacentor genus

Two species of the Dermacentor genus of ticks are most responsible for the transmission of RMSF in the United States. They include Dermacentor variabilis (American dog tick) and Dermacentor andersoni (Rocky Mountain wood tick).

The American dog tick, the primary vector of RMSF, can be found in a large portion of the U.S. that spans east of the Rocky Mountains and limited areas along the west coast. They are found in a variety of habitats including forests, grassy open fields, and low lying brush; however, they are most likely to “quest” or search for a host in areas with high mammalian traffic such as trails or roadsides. American dog ticks hatch from eggs as 6-legged larvae then become 8-legged nymphs before reaching adulthood. A blood meal is required between each life stage and as the tick develops they move from smaller to larger hosts. The American dog tick is unique in that each developmental stage can live for great amounts of time without feeding. Humans commonly encounter the adult stage tick, which can survive up to two years without a blood meal.. American dog ticks are recognizable by their dark brown body with molted, often geometric patterns on the scutum (shield on the back of a hard tick). Males have a molted pattern that extends over the entire scutum, while females only display the molted pattern on the anterior portion of the scutum shield.

Source: CDC – American Dog Tick’s Habitat in the U.S.

The Rocky Mountain wood tick is located in the Rocky Mountain states and parts of southwestern Canada. They can be found in grassy habitats as well as slightly wooded areas. The species appearance is very similar to the American dog tick and will also, most likely, chose a human host only during the adult stage of their lifecycle. The species differ in that the Rocky Mountain wood tick cannot survive as long as the American dog tick without feeding between life stages.

Source: CDC – Rocky Mountain Dog Tick’s Habitat in the U.S.

In addition to being vectors of RMSF, the American dog tick and the Rocky Mountain wood tick are the most common culprits of tick paralysis in North America. Tick paralysis is the only tick-borne disease where an infectious agent was not the cause. Ticks in the above two species contain a neurotoxin in their saliva that can cause paralysis in humans and pets. Unlike other tick-borne diseases, once the tick is removed the individual’s symptoms disappear not long after.

There have also been a small number of RMSF cases where the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus, has been attributed as the vector. While this species can be found throughout the U.S., attributed cases have only been reported from states within the southwest region and along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Individuals and communities should take extra precautions to avoid tick-infested areas, especially during summer months. Dog and cat owners should perform regular tick checks as well as protect them with control products or preventative medication.

Controlling Ticks and Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

Individuals should take extra precautions to avoid tick-infested areas, especially during late spring, summer, and early fall. It seems only logical that control of the tick vectors of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever is mandatory in communities and that lowering these tick populations can significantly reduce the risk of being infected. However, control measures are not always easy or successful because the species Dermacentor ticks that transmit RMSF each have unique and complex life cycles with the ability to transmit diseases during different stages.

VDCI strongly feels that any Integrated Tick Management (ITM) program should strive to control the local population of ticks with minimal impact on the environment and non-target organisms and simultaneously reduce the risk of tick-borne disease transmission. However, because it is impossible to eradicate all ticks given their behavioral patterns, resilient nature and breeding potential, the program’s primary goal should be to manage tick populations within tolerable levels. This reduction is best accomplished through a customized and targeted combination of public education, surveillance, landscape management, and the judicious application of Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) approved pesticides through a variety of techniques and methods.

1: Public Education/Public Relations

Public education is an extremely important facet to the successful implementation of any tick control program. Educational materials that are readily available to the public should detail the various ways people can limit tick exposure and should include information on personal protection as well as awareness and disease information.

2: Inspection and Surveillance

The cornerstone of any successful ITM program is surveillance. Proper identification of tick species and knowledge of their bionomics focuses control efforts on the areas of concern. Potential tick-infesting habitats should be inspected and mapped into a GIS database using GPS technology. After thorough surveillance of the tick and host populations in an area, a more accurate picture of the vector dynamics can be developed and an effective and efficient control plan implemented.

3: Disease Testing

Testing ticks allows us to determine the incidence of tick-borne pathogens that may cause a threat to the health and well-being of residents and visitors to public properties within an area. After pathogen detection, management practices can be developed that will reduce the number of infected ticks and simultaneously reduce the risk of human transmission. VDCI is capable of testing ticks, via approved PCR assays, for a range of common tick-borne pathogens.

4: Control Measures

Successful control of tick populations is dependent on the integration of a number of strategies including host-targeted devices and landscape management. When required, VDCI only applies pesticides approved by the EPA for the control of ticks. These products are delivered by means of hand-held application equipment, such as a spreader or backpack sprayer, and can quickly lower the tick population in targeted areas.

VDCI is a company built on the foundations of public health, ethics, professionalism, and technical expertise. We establish vector management programs that are based on an understanding of the underlying vector’s ecology and rooted in the current science of environmentally sound control measures.

[backlink]