Explore the Mosquito-Borne Diseases Reported In Your Region

Official reports on vector-borne diseases, severe weather, and changes in our climate were repeated in various media outlets last year. The attention brought heightened awareness to a number of disease-carrying pests, with a lot of the attention on – the mosquito. For this article, we will provide a brief overview of mosquito-borne disease reporting to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2018. We will also discuss lesser known mosquito-borne diseases, and the CDC report that highlighted an increase in vector-borne disease reporting over the last decade.

Vector-borne disease transmission cycles are complex. They involve a variety of interconnected environmental parameters – meaning that predicting where they will be prevalent in any given year is difficult. However, we will also briefly cover what is currently being reported in 2019.

Mosquito-Borne Disease Activity Right Now

Before we revisit 2018, you may be curious about the mosquito-borne disease activity at present. As of July 23, 2019, a total of 34 states have reported West Nile virus (WNV) infections in people, birds, or mosquitoes to the CDC. Arizona is already reporting 57 human cases and one human death. With record heat and rains impacting many parts of the U.S. this summer, some communities are experiencing mosquito activity higher than in recent years. Many of the floodwater mosquitoes surfacing are aggressive biters, but they don’t present a health risk. However, there are several mosquito species known to vector disease-causing agents that have communities on alert. Areas with historically high trap counts have program managers seeking additional support – from the ground and the air.

Reno County, KS chose to conduct an aerial adulticide application to reduce Culex populations. Moab, UT chose an aerial mission that focused on reducing larval populations. The goal in Moab was to prevent larvae from emerging and becoming yet another generation of biting adults that could attack a community seeking relief from mosquito populations as well as protection from the diseases they may carry. While a few other mosquito-borne diseases have been detected in the U.S. in 2019, such as eastern equine encephalitis, WNV activity is the majority of mosquito-borne disease reporting across the U.S. at the moment.

Public Health and Vector-Borne Diseases in the U.S.

In May 2018, just ahead of summer outdoor activities and vacations, the CDC released new vector-borne disease statistics in its Vital Signs report. The data in the report reflected a staggering increase in the number of reported vector-borne disease cases. From 2004 to 2016, illnesses reported to the CDC from mosquito, tick, and flea bites more than tripled. The report highlighted the increase in mosquito-borne disease outbreaks in the U.S. as well as the uptick in the number of pathogens/diseases transmitted by these vectors.

The emergence of Zika virus and chikungunya virus in the U.S. were provided as examples. As mosquitoes and the disease they carry are more readily transported through global commerce and travel, and changes in climate create ideal habitats for mosquito species to flourish in new areas of the U.S., more people in the states will be living in areas at risk for mosquito-borne disease transmission. This awareness has community leaders, as well as public health and environmental health professionals, taking action to understand threats in their community and prepare, as much as possible, for the unexpected.

Are Mosquito-Borne Diseases Underreported?

On top of the new data highlighting the increase in the number of vector-borne disease cases reported in the U.S., lesser known mosquito-borne diseases also made headlines in 2018. Two diseases you may not be as familiar with are Keystone virus and Jamestown Canyon virus.

In June 2018, University of Florida researchers announced that the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases had confirmed the first human case of the mosquito-borne Keystone virus. The case stemmed back to August 2016, when a teenage boy presented with a fever and severe rash. Initial tests did not confirm Zika virus or other pathogens. While an isolated case, it may indicate that other mosquito-borne viruses are present and not reported in the U.S.

A wife in New Hampshire watched her husband battle unknown health complications, and he ultimately passed away from encephalitis in June of 2018. A month prior to his death, test results showed evidence of Jamestown Canyon virus (JCV) and his family wonders if the virus was the leading contributor. With so many unknowns and the medical community still learning about the virus, additional research and education continue on JCV.

2018 Mosquito-Borne Diseases Reported to the CDC

As in years past, West Nile virus continues to be the most reported and most deadly mosquito-borne disease in the United States. The remainder of this article will focus on WNV, La Crosse encephalitis, eastern equine encephalitis, St. Louis encephalitis, Jamestown Canyon virus, dengue, and one of the most high-profile diseases covered by the media, addressed by public health organizations, and discussed in communities throughout the U.S.in recent years – Zika virus. Data points for this post were obtained from the CDC’s website as of 07/31/19.

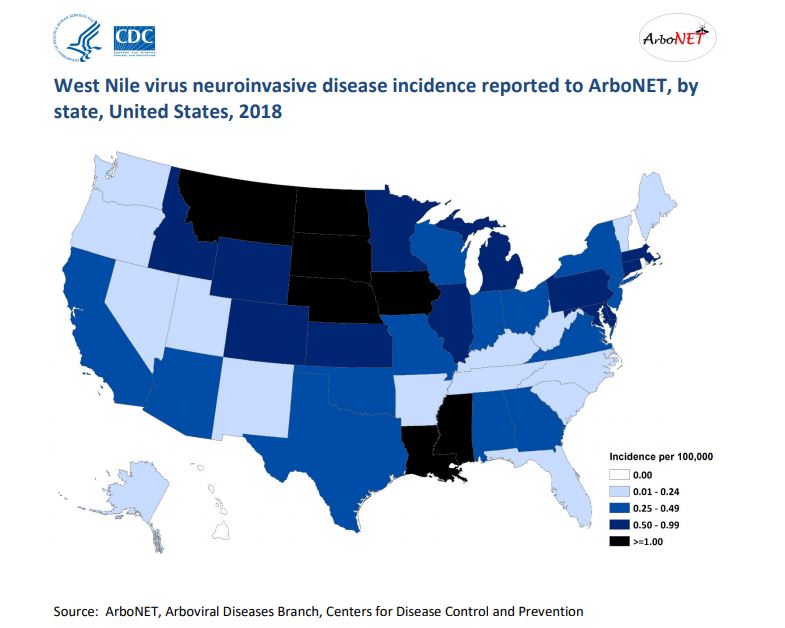

49 out of 50 states and the District of Columbia reported West Nile virus infections in people, birds, or mosquitoes in 2018. Overall, 2,647 cases of WNV were reported in humans, and there were 167 (6.3%) confirmed deaths in 2018. This data shows an increase from the number of human cases reported in 2017 (2,097). It also brings attention to the increase in lives lost, when compared to the 146 (7%) confirmed deaths in 2017 and the 106 (4.9%) confirmed deaths from WNV in 2016.

The states reporting the highest number of human WNV disease cases to the CDC* in 2018:

West Nile Virus 2018 Human U.S. Cases | 2018 Cases | 2018 Deaths |

| Nebraska | 251 | 11 |

| California | 217 | 11 |

| North Dakota | 204 | 2 |

| Illinois | 176 | 17 |

| South Dakota | 169 | 4 |

| Texas | 146 | 11 |

| Pennsylvania | 130 | 8 |

| Iowa | 104 | 9 |

| Michigan | 102 | 9 |

| New York | 98 | 6 |

*Statistics include combined count of Neuroinvasive Disease Cases and Non-neuroinvasive Disease Cases

Illinois reported the most human WNV deaths of any state (17). The second highest reports came from Nebraska, California, and Texas – each reporting eleven (11) deaths. Michigan and Iowa each had nine (9) fatalities related to WNV. Virginia also had a notably high number of fatalities (8) compared to its total number of cases (48).

New Hampshire and Hawaii were the only states that did not report human WNV disease cases to the CDC in 2018.

WNV is typically transmitted to humans by mosquitoes that have previously fed upon an infected bird. While over 150 species of mosquitoes have been known to carry WNV, the main vector species in the U.S. are Culex pipiens, Culex tarsalis, and Culex quinquefasciatus. These mosquitoes are all active at night, and most cases of infection occur during the summer months. Approximately 20% of people affected by WNV will experience flu-like symptoms including fever, headache, nausea, muscle pain, and swollen lymph glands. Other symptoms may include a stiff neck, rash, sleepiness or disorientation. Less than 1% of those infected will develop West Nile Encephalitis or Meningitis, which can lead to coma, tremors, convulsions, paralysis, and even death.

To learn more about the symptoms, treatment, and mosquito species that vector this virus, visit our educational page on West Nile virus.

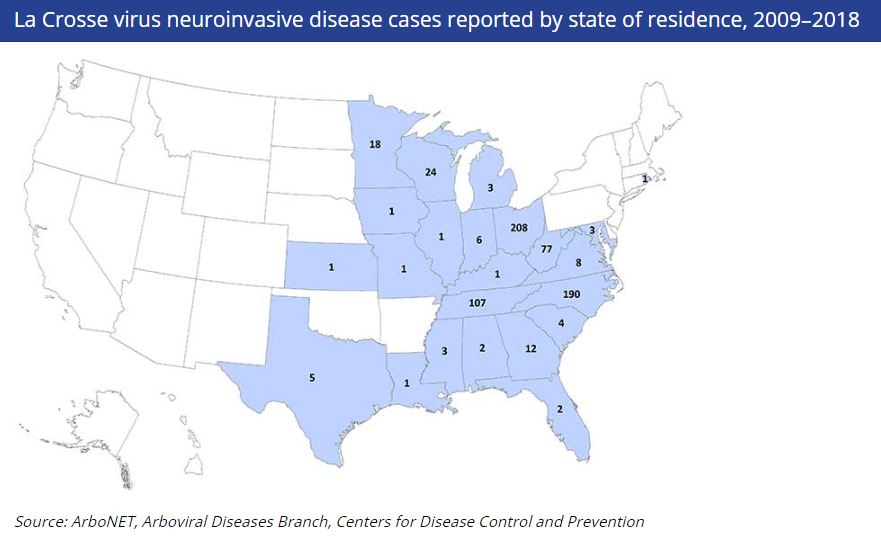

La Crosse Encephalitis Virus (LACV) in 2018

What is mosquito-borne encephalitis?

Mosquito-borne encephalitis can be a severe result of many viruses vectored by mosquitoes. Encephalitis is an inflammation of the brain and central nervous system and is characterized by a high to moderate mortality rate, with some survivors left with permanent physical and mental disabilities. In the U.S., it is geographically wide-spread and is prevalent in several forms: West Nile virus, eastern equine encephalitis, Jamestown Canyon virus, and several others – including La Crosse. Not all individuals who are infected with one of these viruses will have a severe case that results in encephalitis.

Since La Crosse often presents mild or no symptoms after transmission to humans, it is believed that the virus is underdiagnosed and underreported. Because of this, the CDC only uses LACV neuroinvasive disease cases in their statistics.

In 2018, there were 83 human La Crosse virus neuroinvasive disease cases reported in the U.S. The states reporting the most human cases included: Ohio (39), North Carolina (24), and Tennessee (13). There were no human fatalities reported from LACV in 2018.

To learn more about La Crosse encephalitis virus, visit the CDC’s page on LACV.

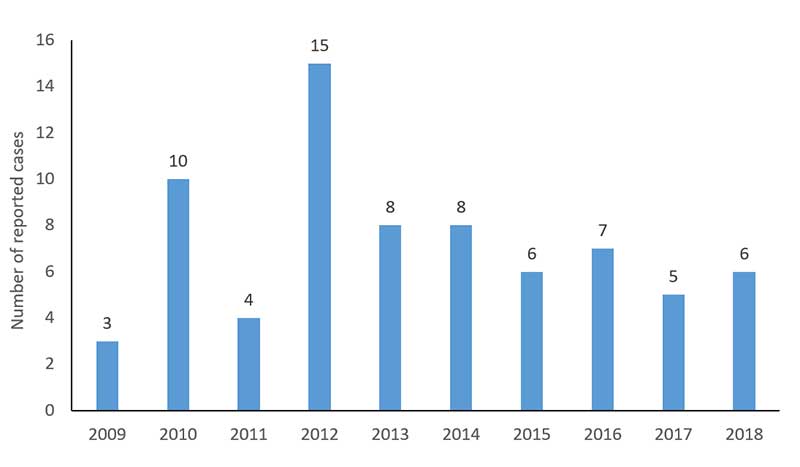

Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE) in 2018

Eastern equine encephalitis, also referred to as EEE or Triple E, is a rare but deadly illness for humans. Thankfully, only a few human cases of EEE are reported in the U.S. each year. From 2009 – 2018, between 3 and 15 cases of EEE were reported to the CDC every year in the U.S. During this time period, Florida (13), Massachusetts (10), New York (8), North Carolina (7), and Michigan (7) reported the highest number of cases.

In 2018, there were 6 reported human cases of EEE and 1 of those cases were fatal.

*Statistics include combined count of Neuroinvasive Disease Cases and Non-neuroinvasive Disease Cases

The reason EEE is less common in humans is that the primary mosquito vector (Culiseta melanura), does not typically feed on humans. It is believed that EEE virus is mainly transmitted to humans and horses by bridge vectors that have contracted the virus by feeding on infected birds. Symptoms typically occur four to ten days after a bite from an infected mosquito and include fever, headache, vomiting, muscle aches, joint pain, and fatigue. In rare cases, infection occurs in the brain and spinal cord leading to sudden high fever, stiff neck, disorientation, seizures, and coma. The mortality rate of those that develop EEE is about 33%, the highest among human arboviruses (a virus transmitted by arthropod vectors) cases reported in the U.S. The disease is also a concern for horses. There is a vaccine available for horses, and horse owners are encouraged to discuss an on-going vaccination schedule with their veterinarians. Currently, there is no human vaccine for EEE.

To learn more about the symptoms, treatment, and mosquito species that vector this virus, visit our educational page on EEE virus.

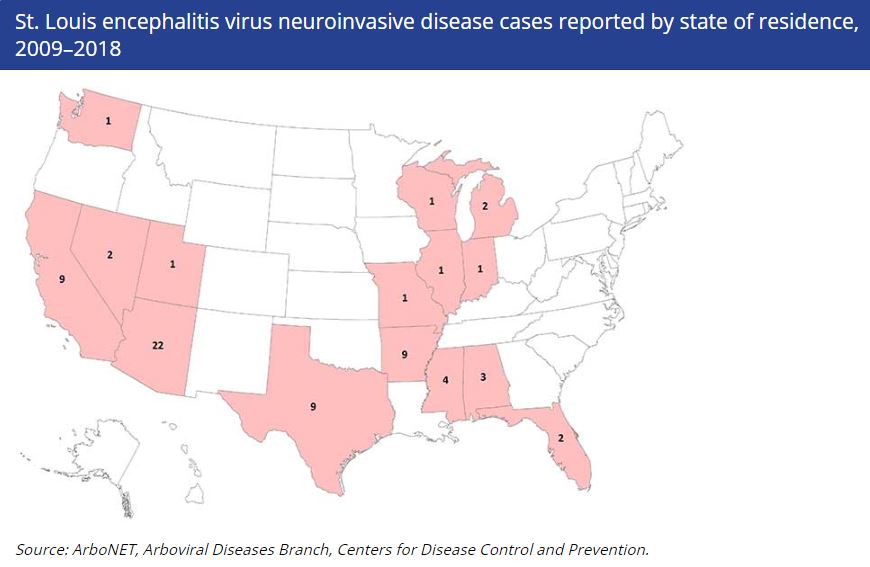

St. Louis Encephalitis (SLE) in 2018

Prior to the introduction of West Nile virus in 1999, St. Louis Encephalitis virus (SLEV) was the most important epidemic mosquito-borne viral disease in the U.S. Annual reports of SLEV cases fluctuate widely, due to periodic epidemics that occur. Most cases occur in west and central states. From 2009 to 2018, an average of seven cases of SLE disease were reported annually. The last major epidemic occurred in 1975 along the Ohio-Mississippi River Basin when nearly 2,000 cases and 142 deaths were reported.

In 2018, there were 8 reported human cases of SLE and 1 of those cases were fatal.

To learn more about the symptoms, treatment, and mosquito species that vector St. Louis encephalitis, visit our educational page on SLE virus.

Jamestown Canyon Virus in 2018

What is interesting about Jamestown Canyon virus (JCV), is that it behaves a little differently than a few of the viruses the public may be more familiar with. West Nile virus (WNV) and Zika virus rely on a reservoir host to perpetuate the virus, as the mosquito cannot pass it on to their offspring. With JCV, in addition to having reservoir hosts, such as deer, this virus can also have transovarian transmission, which means the parent arthropod (in this case a mosquito) can pass the disease pathogen to their offspring. This is not completely uncommon. Rocky Mountain spotted fever is a vector-borne disease that is transmitted through an infected tick carrying the bacterium Rickettsia rickettsii. The bacterium can be transmitted to offspring in this way as well.

JCV was first discovered in Culiseta mosquitoes in Jamestown, Colorado, in 1961. Since 1961, it has been found in various mosquito species (Aedes, Culex, Coquillettidia), mammals, and humans across North America.

In 2018, there were 32 cases of Jamestown Canyon virus reported in the U.S. The majority of the cases were reported from Wisconsin (23).

To learn more about this virus, read our blog on Jamestown Canyon virus.

Zika Virus (ZIKV) in 2018

Overall in 2018, Zika virus (ZIKV) activity slowed within the United States. There were 0 cases of locally-acquired ZIKV and 0 sexually-acquired cases. However, there was continued activity in travel-associated reports of the disease, with 72 travel-acquired cases documented during the year. Over 50% of the travel-acquired cases were from individuals returning to Florida and California from abroad.

U.S. territories also had a substantial drop in reported cases over 2017. In the territories, there were 147 locally-acquired cases and 1 travel-associated case. There were 0 cases reported through other routes. The CDC notes that sexually-acquired cases are not reported for U.S. territories because with local transmission of Zika virus it is not possible to determine whether infection occurred due to mosquito-borne or sexual transmission.

Despite the decreases, VDCI remains vigilant in monitoring ZIKV activity around the globe so that we are able to provide support should another outbreak occur. VDCI partnered with the CDC in several U.S. territories in 2016 to help combat the spread of Zika virus.

Many individuals learned about Zika during the outbreaks in South and North America; however, the virus was first discovered in 1947 in the Zika Forest of Uganda. In the Americas, it has only been linked to transmission by Aedes aegypti or the Yellow Fever mosquito. Ae. aegypti is also responsible for the transmission of dengue virus, yellow fever virus, and chikungunya virus. In other parts of the world, the virus has been detected in Aedes albopictus or the Asian tiger mosquito; hence, it is possible that Ae. albopictus could vector the virus in the Americas.

To learn more about the symptoms, treatment, and mosquito species that vector this virus, visit our educational page on Zika virus.

Dengue Virus in 2018

Dengue virus is transmitted by certain Aedes mosquitoes and considered a major global threat as our world’s urban landscape grows. Beyond the increase in desirable habitats for the container-breeding species, the virus has four strains (multiple serotypes) making it complicated for medical professionals to manage. Chikungunya virus shares similar symptoms to dengue and provides those bitten with immunity from future chikungunya infections. Unfortunately, with multiple strains of dengue, an individual is more likely to be hospitalized or die if infected with more than one serotype. Those previously infected or individuals with a weakened immune system should take even greater precautions.

The United States has experienced local outbreaks of dengue in Hawaii (2015), near the Texas-Mexico border (2013), and in Florida. Except for 2017, Florida reported locally-transmitted cases of dengue annually between 2010 – 2018. Larger outbreaks have occurred within U.S. Territories such as Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and U.S.-affiliated Pacific Islands. A portion of the United States is at a higher risk because of climate and the presence of certain Aedes mosquitoes.

In 2018, there were 2 reported human cases of locally-acquired dengue virus. Texas (1) and Florida (1).

To learn more about the symptoms, treatment, and mosquito species that vector this virus, visit our educational page on dengue.

Monitoring Real-Time U.S. Mosquito-Borne Disease Activity

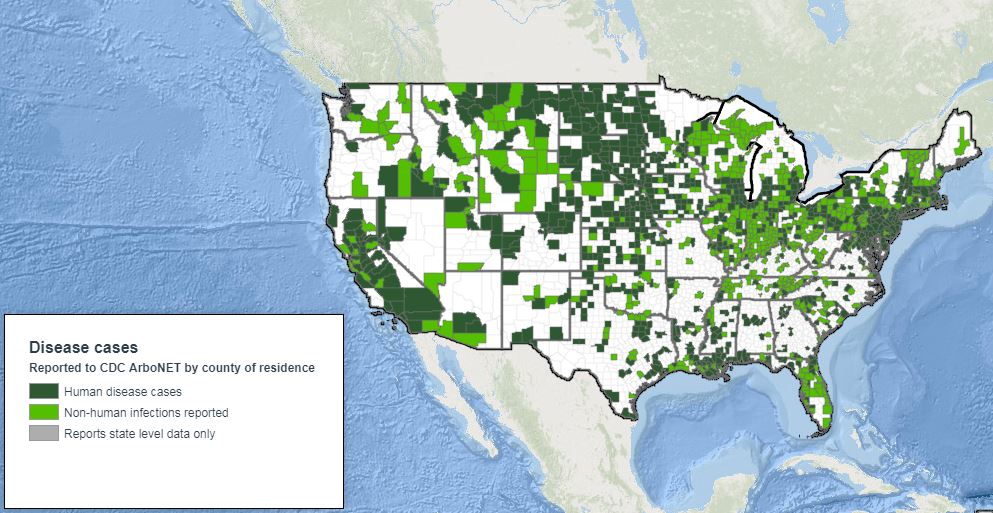

The CDC has a number of tools in place to help citizens and organizations track vector-borne diseases. The CDC’s ArboNet map provides an illustrated overview of mosquito and other vector-borne activity across the U.S. You can view this live map and archival maps which, including:

- West Nile Virus (WNV)

- St. Louis Encephalitis (SLE)

- Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE)

- La Crosse (LAC)

- Dengue (DEN) locally-acquired and travel-associated

- Chikungunya (CHIK) locally-acquired and travel-associated

- Zika Virus (ZIKA) locally-acquired and travel-associated

- Powassan Virus (a tick-borne disease)

Utilize the tabs across the top of the ArboNet map to choose the specific vector-borne disease to track and the drop-down menu at the right to select the year. Note: There are times where the CDC’s disease page and the ArboNet map are not in sync. It can be beneficial to reference both resources to ensure you have the most up-to-date disease reporting. Communities may also report disease cases and probably diseases cases on their individual website prior to reporting to the CDC. We encourage all individuals to take personal protection measures and monitor local disease activity via resources available within your community.

This 2018 map from CDC’s ArboNet shows West Nile virus activity across the U.S. in 2018.

VDCI is committed to public education and spreading awareness throughout the U.S. about the dangers of mosquito-borne diseases and their preventability, with the overarching goal of reducing illness and fatality statistics. Our dedicated and experienced team works tirelessly with local governments to prevent the spread of mosquito-borne diseases in all of the contracts we service from coast to coast. We hope everyone has a safe summer.

If you would like more information about any aspect of an Integrated Mosquito Management (IMM) Plan, including mosquito surveillance, disease testing, adult control, aerial applications, resistance testing, or creating an emergency response plan (major flood event or disease outbreak) – please contact Vector Disease Control International (VDCI).

In addition, our team has played an integral role in disaster relief and disease outbreak situations for over 20 years. With our fleet of over 200 trucks and 12 aircraft, VDCI is the only company in the country that can internally manage all aspects of an integrated mosquito management program, from surveillance and disease testing to ground and aerial operations for seasonal needs or emergency response situations.

We are determined to protect the public health of the communities in which we operate.

Contact Us to Learn More About Effective Mosquito Management Strategies:

Since 1992, Vector Disease Control International (VDCI) has taken pride in providing municipalities, mosquito abatement districts, industrial sites, planned communities, homeowners associations, and golf courses with the tools they need to run effective mosquito control programs. We are determined to protect the public health of the communities in which we operate. Our mosquito control professionals have over 100 years of combined experience in the field of public health, specifically vector disease control. We strive to provide the most effective and scientifically sound mosquito surveillance and control programs possible based on an Integrated Mosquito Management approach recommended by the American Mosquito Control Association (AMCA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). VDCI is the only company in the country that can manage all aspects of an integrated mosquito management program, from surveillance to disease testing to aerial application in emergency situations.

Since 1992, Vector Disease Control International (VDCI) has taken pride in providing municipalities, mosquito abatement districts, industrial sites, planned communities, homeowners associations, and golf courses with the tools they need to run effective mosquito control programs. We are determined to protect the public health of the communities in which we operate. Our mosquito control professionals have over 100 years of combined experience in the field of public health, specifically vector disease control. We strive to provide the most effective and scientifically sound mosquito surveillance and control programs possible based on an Integrated Mosquito Management approach recommended by the American Mosquito Control Association (AMCA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). VDCI is the only company in the country that can manage all aspects of an integrated mosquito management program, from surveillance to disease testing to aerial application in emergency situations.