Mosquito Species Deep Dive

High in the Rocky Mountains, under the snow and ice, eggs that were laid by mosquitoes last summer lay dormant, waiting for spring. As soon as the ice becomes liquid, the first of the eggs will hatch.

High in the Rocky Mountains, under the snow and ice, eggs that were laid by mosquitoes last summer lay dormant, waiting for spring. As soon as the ice becomes liquid, the first of the eggs will hatch.

Known as the snowmelt mosquitoes, these species have a short season in which to grow. In order to get a head start, the larvae are adapted to survive in very cold water, including snowmelt ponds and overflow pools from frigid mountain streams. The cold water slows down their metabolism as well as their development into a flying, biting adult mosquito, which can take several weeks.

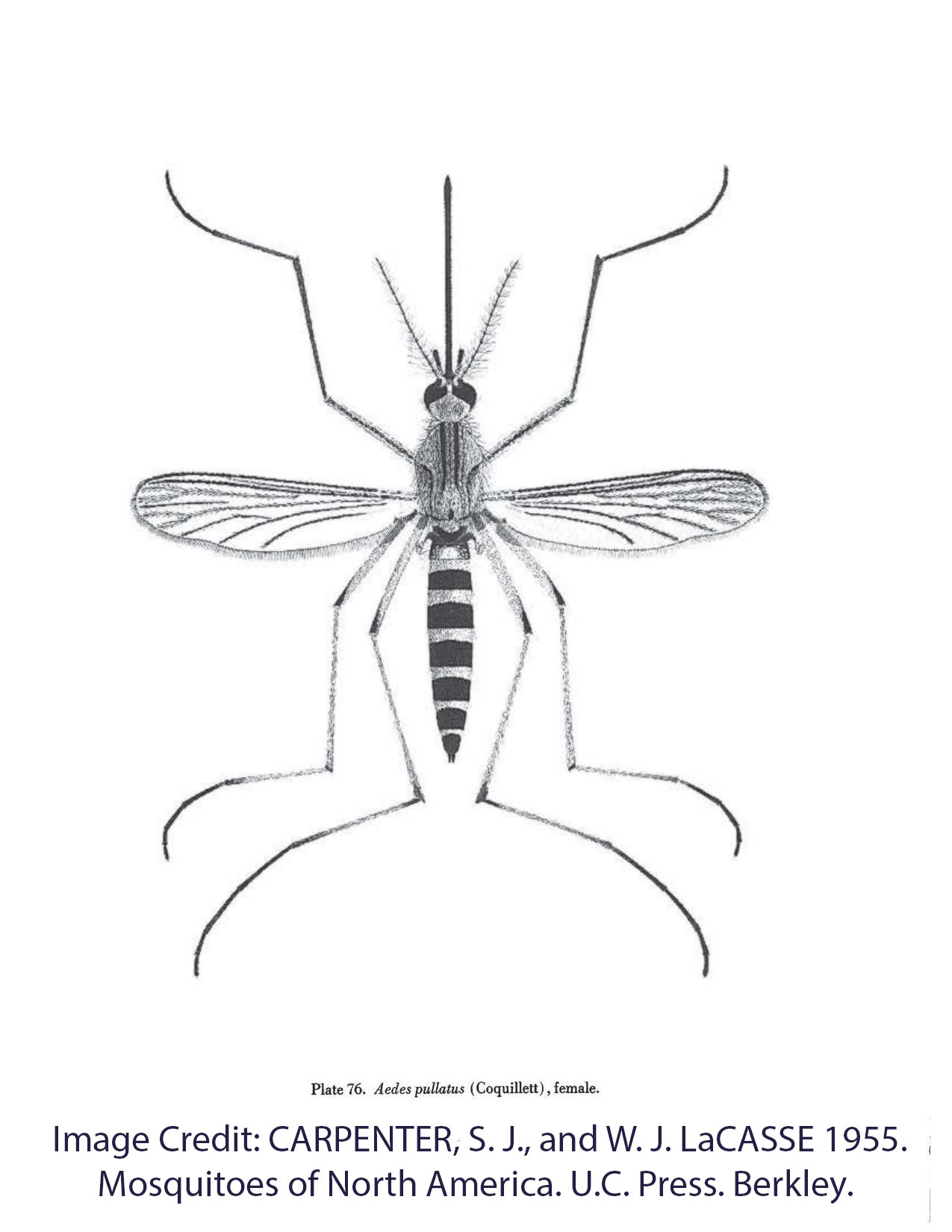

One of the most widespread, and arguably most beautiful of these cold-adapted species, is the Alpine Snowmelt Mosquito, Aedes pullatus. This mosquito is often abundant throughout the summer in mountainous areas of western North America, Europe, and Asia. They occur mainly in higher elevations, although also found less commonly as low as sea level in the colder northern latitudes.

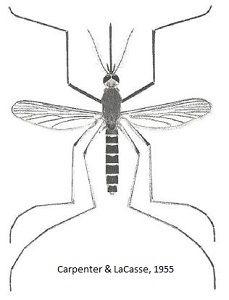

Yes, I did say “arguably most beautiful.” Most of the high altitude mosquitoes are primarily black-scaled with only a few scattered patches of pale scales, their dark coloration perhaps being an adaptation for maximizing heat absorption. Aedes pullatus is also primarily dark-scaled, but is adorned with white, golden, and yellow patches of scales on the top and sides of its thorax. The top of their abdomen also has distinct white-scaled basal bands on each segment. On a microscopic scale, these mosquitoes stand out from most other mountain species – beautiful.

Snow doesn’t melt all at once, and often pools created by the first melting snow on sunny spring days will again freeze by cold night temperatures or late spring snow falls. Few animals can survive this repeated freezing and thawing, but I have found these alpine snowmelt mosquito larvae in the spring by chipping away at an ice-covered pond. Under the ice they were moving slowly but very much alive.

Adults emerge throughout the summer. Males of this species have been reported to hover in great swarms just after sunset, often over a boulder or other solid landmarks in a forest opening, waiting for a receptive female to fly through the crowd. The resulting scramble results in one fast, lucky male getting to mate with her and father her next set of eggs – it isn’t known whether the female mates only once or if they seek out other males in the future. We also don’t know how long they live, or how many eggs females may lay in their lifetime.

In fact, relatively very little is known about the biology and behavior of alpine snowmelt mosquitoes when compared to some of the more economically or medically important mosquito species that have been better studied. Aedes pullatus are among the least studied mosquitoes, not currently known to vector any human diseases, and only a biting nuisance locally. If you happen to be in the right mountain forest, at the right time of year, you may encounter large numbers of these blood-hungry female mosquitoes, but otherwise they go about their lives unnoticed by most people.

In fact, relatively very little is known about the biology and behavior of alpine snowmelt mosquitoes when compared to some of the more economically or medically important mosquito species that have been better studied. Aedes pullatus are among the least studied mosquitoes, not currently known to vector any human diseases, and only a biting nuisance locally. If you happen to be in the right mountain forest, at the right time of year, you may encounter large numbers of these blood-hungry female mosquitoes, but otherwise they go about their lives unnoticed by most people.

Perhaps future researchers studying cryogenics or cold-tolerance in animals would find these mosquitoes to be fascinating organisms to work with, but otherwise they are not likely to attract much attention. At least for this mosquito researcher, whenever I have the opportunity to visit the mountains in the springtime, I will continue to peek under the ice and marvel at these cold-adapted insects.

Contact Us to Learn More About Effective Mosquito Management Strategies:

Since 1992, Vector Disease Control International (VDCI) has taken pride in providing municipalities, mosquito abatement districts, industrial sites, planned communities, homeowners associations, and golf courses with the tools they need to run effective mosquito control programs. We are determined to protect the public health of the communities in which we operate. Our mosquito control professionals have over 100 years of combined experience in the field of public health, specifically vector disease control. We strive to provide the most effective and scientifically sound mosquito surveillance and control programs possible based on an Integrated Mosquito Management approach recommended by the American Mosquito Control Association (AMCA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). VDCI is the only company in the country that can manage all aspects of an integrated mosquito management program, from surveillance to disease testing to aerial application in emergency situations.

Since 1992, Vector Disease Control International (VDCI) has taken pride in providing municipalities, mosquito abatement districts, industrial sites, planned communities, homeowners associations, and golf courses with the tools they need to run effective mosquito control programs. We are determined to protect the public health of the communities in which we operate. Our mosquito control professionals have over 100 years of combined experience in the field of public health, specifically vector disease control. We strive to provide the most effective and scientifically sound mosquito surveillance and control programs possible based on an Integrated Mosquito Management approach recommended by the American Mosquito Control Association (AMCA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). VDCI is the only company in the country that can manage all aspects of an integrated mosquito management program, from surveillance to disease testing to aerial application in emergency situations.

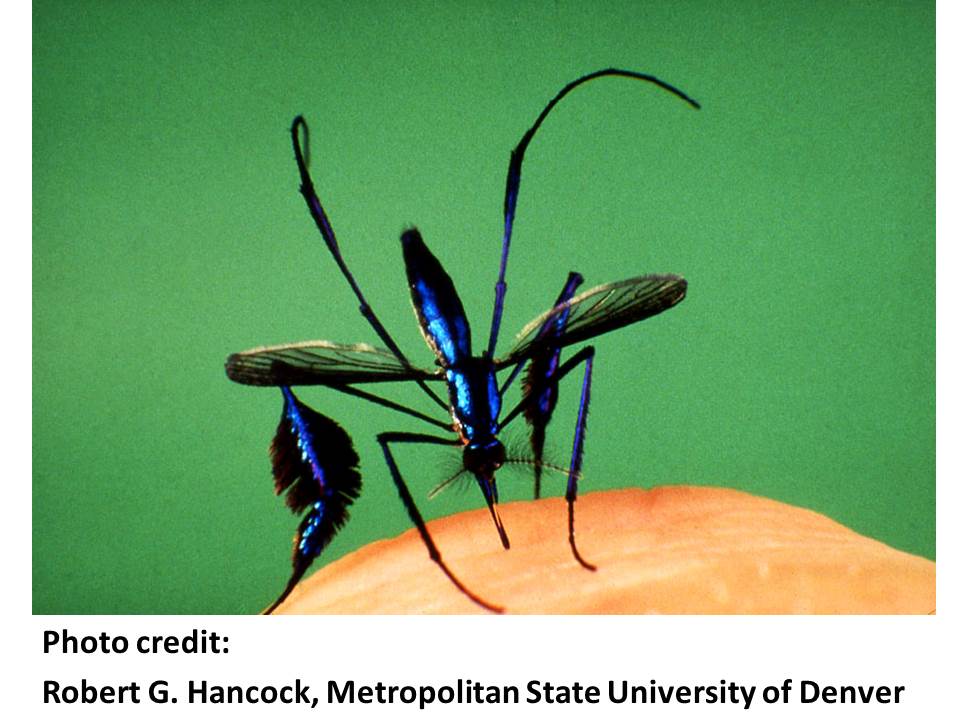

There is one notable exception, the paddle-legged beauty, Sabethes cyaneus. This tropical forest species lay their eggs in shaded natural and artificial containers such as tree-holes, bamboo hollows, and even fallen banana leaves filled with rainwater. Sabethes larvae develop in these small

There is one notable exception, the paddle-legged beauty, Sabethes cyaneus. This tropical forest species lay their eggs in shaded natural and artificial containers such as tree-holes, bamboo hollows, and even fallen banana leaves filled with rainwater. Sabethes larvae develop in these small  Dr. Hancock’s team described the unique and elaborate series of stereotypical behaviors displayed by Sabethes mosquitoes prior to and during

Dr. Hancock’s team described the unique and elaborate series of stereotypical behaviors displayed by Sabethes mosquitoes prior to and during

It is winter and all the

It is winter and all the