Discover the Changes In Mosquito Behaviors

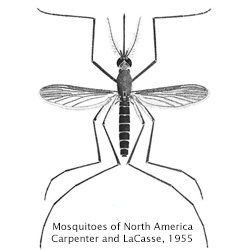

Generally, in Colorado, we spend day after day digging through piles of Aedes vexans, Culex pipiens, Culex tarsalis, and several other common species. When it comes to adult mosquito surveillance, our Denver office alone sets and collects over 200 traps per week. It can get pretty exciting while sorting through a pile of mosquitoes, during your normal monotonous routine, when a specimen that doesn’t seem to belong appears under your microscope. After running the unique arthropod through a dichotomous key (an identification tool), the excitement is heightened when you realize you have found a mosquito species never previously recorded in your state! In a single season, our Denver lab identified three (3) species that lacked historical records in the state of Colorado. Needless to say, our team was intrigued by the new discoveries and took on the challenge to monitor their presence during the remainder of the season as well as throughout the next year.

The obvious question was, “Why are new species entering Colorado?” The state has seen a substantial increase in people moving in over the last decade. Could the influx of human residents be playing a role in the introduction of the 6-legged residents? Are changes by Mother Nature contributing to the mosquito species crossing state lines? Or a combination of the above?

Whether the species was a single specimen, only visiting for the season, or have established a new presence within the state – our team of mosquito detectives enjoyed monitoring the unique finds over the last two seasons. We hope you learn something new about each species as well as appreciate our team’s perspective on the potential reasons for each species to explore a new region of the country.

Species: Orthopodomyia signifera

Primary Territory: Eastern and Southern United States

2017 Colorado Location: South-Central Colorado

Or. signifera is a tree-hole species. The species prefers to utilize nature-made containers as their larval habitats – primarily tree holes. The discovery of the species (a single specimen) in the Colorado town of Pueblo was a surprise. The region is a desert environment that has historically lacked trees, except along the streams. These riparian areas (locations adjacent to rivers or streams) were either flooded away after the spring snowmelt, cut to be burned for fuel, or used as building materials, such that the trees never grew large enough to have hollows that could hold water.

Or. signifera is a tree-hole species. The species prefers to utilize nature-made containers as their larval habitats – primarily tree holes. The discovery of the species (a single specimen) in the Colorado town of Pueblo was a surprise. The region is a desert environment that has historically lacked trees, except along the streams. These riparian areas (locations adjacent to rivers or streams) were either flooded away after the spring snowmelt, cut to be burned for fuel, or used as building materials, such that the trees never grew large enough to have hollows that could hold water.

During the 2017 season, we found the Or. signifera specimen along the Arkansas River where trees now grow. The river’s water levels are now controlled by upstream dams and diversion, therefore rarely flooding even during the spring snowmelt runoff, and they are no longer harvested for building materials or fuel. Today, trees in this area are encouraged to grow to maturity due to the changes humans have made to the environment. Therefore they provide the cracks and hollows Orthopodomyia require to reproduce. The 2017 discovery was a single record.

2018 Colorado Update: Unfortunately, we did not find any more specimens of this species during the 2018 season – which limits our ability to understand how or why the first specimen was located in the region. It could represent an accidental introduction of a stowaway mosquito, brought to the state by a human driving a car or truck from a more suitable southern location; however, this does not necessarily mean Or. signifera aren’t established here. Tree hole species are not usually collected in traps in high numbers. This could have been an isolated incident, but only time will tell.

Species: Culiseta minnesotae

Primary Territory: The northern United States, especially in the colder regions of the Midwest, and into the Canadian prairie.

2017 Colorado Location: North-Central Colorado

While Colorado has suitable habitat for Culiseta minnesotae, the species has never been recorded in the state and is suspected to be adapted to a colder climate. Our team collected Cs. minnesotae in the City of Boulder within an open space that previously was a ranch. Colorado is way out of range for this species; in fact, this is the most southern location it has been recorded. This species is quite large and adapted for taking blood meals from larger mammals such as ungulates (which include deer as well as cattle and other livestock), so it makes sense to find it where horses used to reside. We’ve only collected it at one particular trap site. However, it was collected at this site multiple times during the 2017 season.

While Colorado has suitable habitat for Culiseta minnesotae, the species has never been recorded in the state and is suspected to be adapted to a colder climate. Our team collected Cs. minnesotae in the City of Boulder within an open space that previously was a ranch. Colorado is way out of range for this species; in fact, this is the most southern location it has been recorded. This species is quite large and adapted for taking blood meals from larger mammals such as ungulates (which include deer as well as cattle and other livestock), so it makes sense to find it where horses used to reside. We’ve only collected it at one particular trap site. However, it was collected at this site multiple times during the 2017 season.

2018 Colorado Update: Our team did not find any Cs. minnesotae during the 2018 season. The 2017 population may have been an isolated introduction, perhaps brought to the former ranch location by a horse trailer from the north. However, collecting Cs. minnesotae for multiple consecutive weeks in 2017 does tell us this species can survive here, although it probably has not established a permanent population.

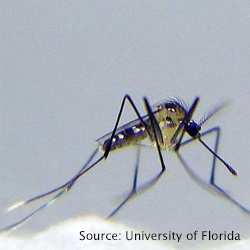

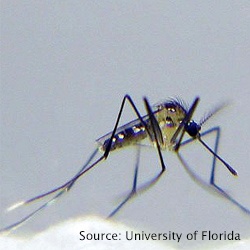

Species: Aedes sollicitans (Salt Marsh Mosquito)

Primary Territory: Along the Atlantic coast from northeastern Canada, south to Florida, and along the Gulf of Mexico to Texas.

2017 Colorado Location: Eastern Colorado

Coastal locations are common for Aedes sollicitans as the larvae live in brackish water. They can occur inland in isolated populations from somewhat saline waters created by other non-marine sources such as runoff from over-fertilization, roadside ditches where salt is used to melt ice, and wastewater from oil and gas wells.

Coastal locations are common for Aedes sollicitans as the larvae live in brackish water. They can occur inland in isolated populations from somewhat saline waters created by other non-marine sources such as runoff from over-fertilization, roadside ditches where salt is used to melt ice, and wastewater from oil and gas wells.

Our team found Ae. sollicitans in half a dozen different traps from different parts of the eastern portion of the state in 2017. It looks like a more common species that live as larvae in flooded pastures, so a couple of things could be happening here. Perhaps it has always been here, and we have been misidentifying it as Aedes nigromaculis, a species that looks very similar to the untrained eye. However, being so far from the coast, that doesn’t explain where the larvae are living. For that, we look at the expansion of irrigated agriculture, roadside ditches, and oil and gas exploration. All of the traps that collected Ae. sollicitans are in close proximity to one or more of these kinds of human-altered habitats.

2018 Colorado Update:

Since the first Ae. sollicitans record was found in Colorado, we have collected many specimens for two consecutive seasons. It is likely established here, which is not surprising as this species is known to be moving inland for quite some time now. As our Chief Entomologist, Doc Weissmann mentions, in his Mosquito of the Month blog series, Ae. sollicitans in other parts of the country have been identified 30 to as far as 100 miles from their likely breeding habitats. This species is opportunistic. If the proper habitat and niche are provided in a new area – it will thrive. While we haven’t detected a disease threat in the samples collected in Colorado, this aggressive biting species has been identified in other areas of the country as a competent vector of Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE) and dog heartworm.

The three (3) species discovered by the Denver lab made for an interesting 2017 season and kept our team intrigued throughout the 2018 season. As humans continue to alter habitat and make changes to the environment, we can expect to see more species establish in areas out of their known range, or at least make a brief appearance in the future. People will also continue to transport species from place to place. Transportation can occur with stowaways in a vehicle or hidden within products used for many trades. Some species have been known to lay their eggs on sod. The landscaping material gets wrapped up and shipped out to multiple states and simultaneously moves that species to a new area. Used tires have allowed the notorious Aedes albopictus (Asian Tiger mosquito) and Aedes aegypti (Yellow Fever mosquito) to increase their range as tires are transported to recycling facilities across the country.

The three (3) species discovered by the Denver lab made for an interesting 2017 season and kept our team intrigued throughout the 2018 season. As humans continue to alter habitat and make changes to the environment, we can expect to see more species establish in areas out of their known range, or at least make a brief appearance in the future. People will also continue to transport species from place to place. Transportation can occur with stowaways in a vehicle or hidden within products used for many trades. Some species have been known to lay their eggs on sod. The landscaping material gets wrapped up and shipped out to multiple states and simultaneously moves that species to a new area. Used tires have allowed the notorious Aedes albopictus (Asian Tiger mosquito) and Aedes aegypti (Yellow Fever mosquito) to increase their range as tires are transported to recycling facilities across the country.

These are just a couple of examples of how our impact as humans expands the geographic range of mosquitoes. As mentioned with the Orthopodomyia signifera discovery – we may have isolated incidents, but only time will tell how much of an impact that humans, as well as naturally occurring environmental changes, will have on the creation of new mosquito habitats and territories.

Contact Us to Learn More About Effective Mosquito Management Strategies:

Since 1992, Vector Disease Control International (VDCI) has taken pride in providing municipalities, mosquito abatement districts, industrial sites, planned communities, homeowners associations, and golf courses with the tools they need to run effective mosquito control programs. We are determined to protect the public health of the communities in which we operate. Our mosquito control professionals have over 100 years of combined experience in the field of public health, specifically vector disease control. We strive to provide the most effective and scientifically sound mosquito surveillance and control programs possible based on an Integrated Mosquito Management approach recommended by the American Mosquito Control Association (AMCA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). VDCI is the only company in the country that can manage all aspects of an integrated mosquito management program, from surveillance to disease testing to aerial application in emergency situations.

Since 1992, Vector Disease Control International (VDCI) has taken pride in providing municipalities, mosquito abatement districts, industrial sites, planned communities, homeowners associations, and golf courses with the tools they need to run effective mosquito control programs. We are determined to protect the public health of the communities in which we operate. Our mosquito control professionals have over 100 years of combined experience in the field of public health, specifically vector disease control. We strive to provide the most effective and scientifically sound mosquito surveillance and control programs possible based on an Integrated Mosquito Management approach recommended by the American Mosquito Control Association (AMCA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). VDCI is the only company in the country that can manage all aspects of an integrated mosquito management program, from surveillance to disease testing to aerial application in emergency situations.

In contrast to the beautiful, benign

In contrast to the beautiful, benign

Much like its overly-sized relative, the pale-footed Uranotaenia has no interest in humans. This lack of interest, combined with its small size, leaves the species often unnoticed in

Much like its overly-sized relative, the pale-footed Uranotaenia has no interest in humans. This lack of interest, combined with its small size, leaves the species often unnoticed in

But fear not – these giant, day-flying mosquitoes do not need a blood meal to produce eggs, so they do not bite. Due to their lack of interest in taking a nibble, they are only caught in certain kinds of traps associated with

But fear not – these giant, day-flying mosquitoes do not need a blood meal to produce eggs, so they do not bite. Due to their lack of interest in taking a nibble, they are only caught in certain kinds of traps associated with

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 1,500 cases of malaria are diagnosed each year in the U.S., predominantly in travelers or immigrants coming from countries where malaria transmission is common, primarily from sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Could malaria make a come-back in this country? It is not out of the realm of possibility. The malaria parasite (Plasmodium) that causes the disease symptoms in humans was almost eliminated in North America through targeted

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 1,500 cases of malaria are diagnosed each year in the U.S., predominantly in travelers or immigrants coming from countries where malaria transmission is common, primarily from sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Could malaria make a come-back in this country? It is not out of the realm of possibility. The malaria parasite (Plasmodium) that causes the disease symptoms in humans was almost eliminated in North America through targeted

The name “vexans” is from the Latin word “vexāre” meaning to annoy, torment, or harass. In many parts of the world, this species is a major nuisance, the females biting in the evening, peaking in activity an hour or so after sunset. They are opportunistic feeders, taking blood meals from a variety of animals as available, but apparently preferring larger mammals, including cattle, horses, deer, and humans when present.

The name “vexans” is from the Latin word “vexāre” meaning to annoy, torment, or harass. In many parts of the world, this species is a major nuisance, the females biting in the evening, peaking in activity an hour or so after sunset. They are opportunistic feeders, taking blood meals from a variety of animals as available, but apparently preferring larger mammals, including cattle, horses, deer, and humans when present. This is the classic “floodwater” mosquito species. By floodwater, it means that they lay their eggs individually on moist soil above the waterline at a wide variety of aquatic habitats, including temporary pools such as detention ponds or irrigated fields, but also permanent water bodies where the water level fluctuates. They especially prefer to lay eggs where there is a lot of leaf and twig cover, helping to keep the soil moist. After a short period of drying, the eggs must subsequently be flooded with water to hatch. During periods of drought, eggs can remain dormant but viable for many years, waiting for the water to rise. Extreme flooding, like the recent natural disaster in West Virginia, may wash away dormant eggs or provide water levels that welcome several new generations of Aedes vexans – only time will tell.

This is the classic “floodwater” mosquito species. By floodwater, it means that they lay their eggs individually on moist soil above the waterline at a wide variety of aquatic habitats, including temporary pools such as detention ponds or irrigated fields, but also permanent water bodies where the water level fluctuates. They especially prefer to lay eggs where there is a lot of leaf and twig cover, helping to keep the soil moist. After a short period of drying, the eggs must subsequently be flooded with water to hatch. During periods of drought, eggs can remain dormant but viable for many years, waiting for the water to rise. Extreme flooding, like the recent natural disaster in West Virginia, may wash away dormant eggs or provide water levels that welcome several new generations of Aedes vexans – only time will tell. Depending on the year, Aedes vexans mosquitoes constitute 40 – 50% of the tens of thousands of specimens that I examine under my microscope each summer in my role as a mosquito surveillance entomologist in Colorado. A familiar foe, it has demonstrated an ability to adapt to a wide variety of habitats, natural and human-made. While our

Depending on the year, Aedes vexans mosquitoes constitute 40 – 50% of the tens of thousands of specimens that I examine under my microscope each summer in my role as a mosquito surveillance entomologist in Colorado. A familiar foe, it has demonstrated an ability to adapt to a wide variety of habitats, natural and human-made. While our

Adults of both rock pool mosquito species have primarily black-scaled bodies with distinct white bands on the base of each abdominal segment, and white banding on either side of the leg joints. The two species differ only subtly in details that only a nerdy entomologist would notice while looking at them under a microscope – the distance between their eyes, the relative proportion of black to white scales on the femur of the hind legs, and the presence or absence of bristly hairs on the back of the thorax. Differences between the larvae are even more difficult to distinguish, including the number of spines, known as comb scales, which adorn the end of the abdomen.

Adults of both rock pool mosquito species have primarily black-scaled bodies with distinct white bands on the base of each abdominal segment, and white banding on either side of the leg joints. The two species differ only subtly in details that only a nerdy entomologist would notice while looking at them under a microscope – the distance between their eyes, the relative proportion of black to white scales on the femur of the hind legs, and the presence or absence of bristly hairs on the back of the thorax. Differences between the larvae are even more difficult to distinguish, including the number of spines, known as comb scales, which adorn the end of the abdomen. Some rock pool mosquitoes have found

Some rock pool mosquitoes have found

As its name implies, the Eastern Saltmarsh Mosquito is found primarily along the Atlantic coast from northeastern Canada, south to Florida, and along the Gulf of Mexico to Texas. The larvae tolerate living in the saline wetlands that line the coastal shores, from dense marshes covering

As its name implies, the Eastern Saltmarsh Mosquito is found primarily along the Atlantic coast from northeastern Canada, south to Florida, and along the Gulf of Mexico to Texas. The larvae tolerate living in the saline wetlands that line the coastal shores, from dense marshes covering